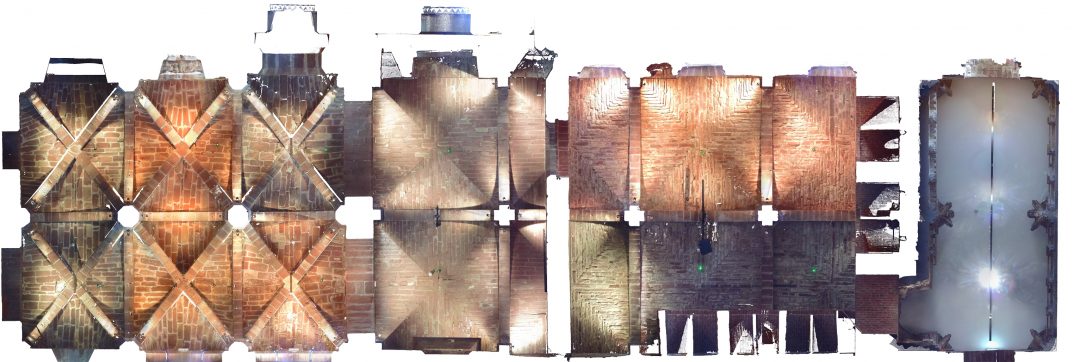

Whilst our project is principally concerned with the stonework of medieval vaulting, this was not the only material used by medieval masons. Whereas stone possesses a high compressive strength, it has a low tensile strength and tends to fracture when bent. Consequently, medieval masons needed to use other materials in order to compensate for the limitations of the stone. Mortar was used to bind the stones together, with ironwork occasionally providing additional support. Wood was used extensively for roofs, scaffolding and centering, as well as occasionally for the vaults themselves. By combining the properties of these different materials, medieval masons were able to construct increasingly elaborate vault designs. The demand resulted the development of a thriving construction industry, with both local and continental European sources being used to supply building materials.

Stone

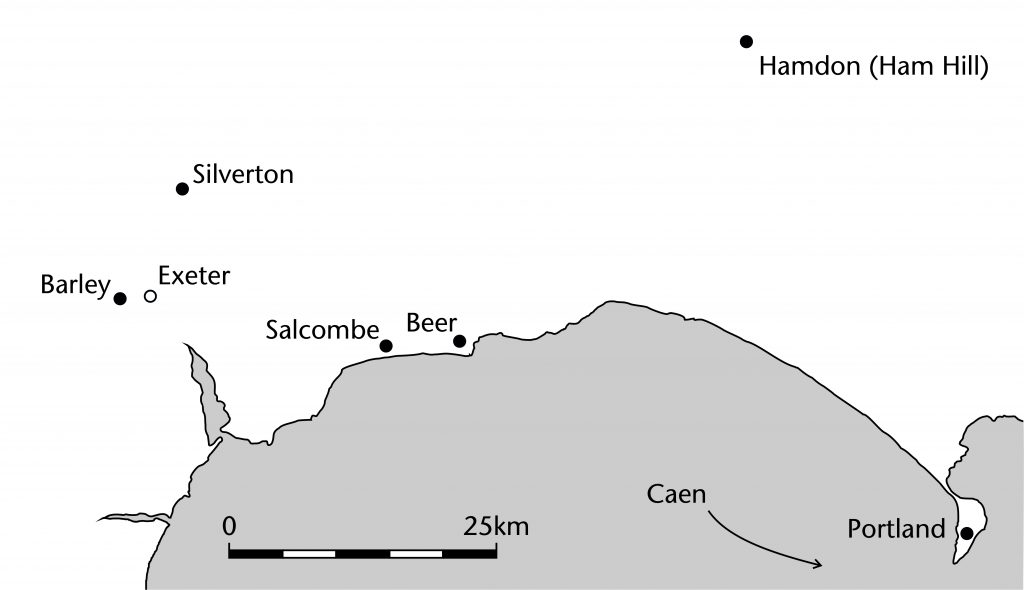

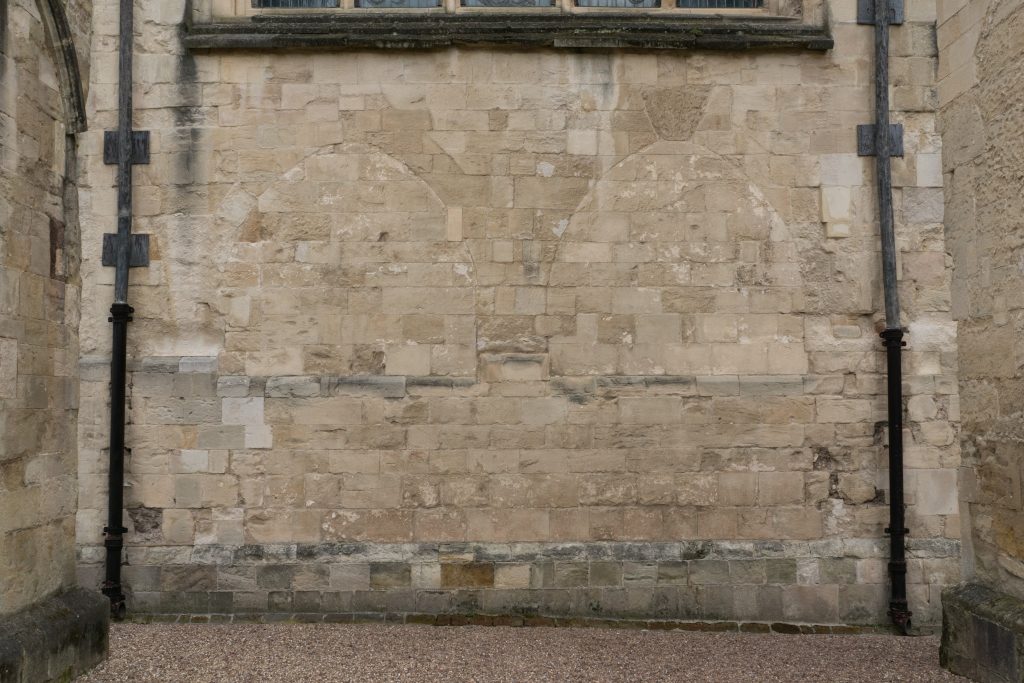

Whilst many different types of stone were used in medieval vaulting, the most common for ribs and bosses was finely grained limestone. This usually provided the best balance of properties for stonework, being hard enough to hold its shape yet soft enough to support fine carving without compromising the durability of the masonry. For the webbing, however, lighter stones were typically used. In the nave at Exeter the webs were made from trap, a reddish volcanic stone honeycombed with tiny holes, whereas in some of the vaults in the cathedrals at at Worcester, Canterbury, Rochester And Salisbury tufa was used. Whilst such stones could often be sourced locally, in many cases it was transported over great distances by land and sea. At Exeter several different quarries were used to supply stone for the cathedral vaults, including nearby sources at Barley, Salcombe, Silverton and Beer as well as more distant ones such as Hamdon, Portland or Caen in Normandy.

Quarrying usually took place in large open-cast pits, though on occasion tunnelling would have been used to extract the stone from underground. Wells would be dug to identify deposits and horizontal tunnels would be cut to meet them, with collapses being prevented by columns of untouched stone. Stone would be extracted from the face using a combination of axes, adzes, crowbars and iron wedges driven in by mallets before being broken or sawn into individual blocks. The blocks would be roughly squared or ‘scappled’ into various shapes and sizes by the quarrymen, then either be transported directly to the worksite or dressed at the quarry.

There were three distinct types of stones used for making medieval vaulting. The first were the finely carved components of vault ribs, specifically the voussoirs, bosses and tas-de-charge stones. These were usually cut from selected limestone blocks, with their sculptural elements sometimes cut by specialist masons. Webbing was conventionally made from ashlar masonry, stones that were cut or ‘dressed’ into regular square blocks with a smooth surface. Sometimes, however, the webbing was be made using roughly cut, irregular pieces of stone known as rubble.

Rubble would most commonly be used for infilling, both between the outer and inner surfaces of the walls and in the pockets of the vault. In the choir, transept and nave vaults of Westminster Abbey chalk was used, providing a soft, compressible medium for the infilling. However, stone was not the only material which was available for infilling. At some sites such as Norwich Cathedral Cloister bricks or tiles were used to fill the vault pockets.

Mortar

The mortar used in medieval vaulting was a mixture of lime and sand. Lime was made by burning chalk or limestone and was usually bought readymade. Sand was extracted from quarries, river beds and the sea-shore. The mortar would be fixed on site, using riddles or sieves to sift the sand and lime before mixing them with water.

Mortar was generally used in two different ways. For dressed stone such as ribs or wall facing it was conventionally applied in thin layers. For rubble infill, by contrast, it would be poured in large quantities, forming a kind of concrete beneath the ashlar surface of the wall or above the vault webs.

Iron

Ironwork was occasionally used by medieval masons for fixing stones together, performing a function similar to reinforcing rods in modern concrete building. This can be seen in some of the ridge ribs in the choir at Exeter, where the joints were cramped with iron spikes set in molten lead. Iron nails were also often used in woodwork, including the fabric of roofs, scaffolding and centering.

Wood

Not all medieval vaults were made of stone. Wooden vaulting was more widespread than is often assumed during the Middle Ages, especially in England. The ribs and supporting structure were usually built using oak timbers, with oak planks used for the webbing in between. Oak timbers were also used extensively for the roofs above and the centering used to erect the vault, with alder often being used for the scaffolding.

Wood is particularly useful from a historical standpoint because it can often be dated using dendrochronology. Consequently, many of the dates assigned to vaults are derived from those of the roof structures above them.

Further reading

- Alexander, J. (1995b) ‘Building Stone from the East Midlands Quarries: Sources, Transportation and Usage’, Medieval Archaeology 39, pp. 107-35.

- Allan, J. (1991) ‘A Note on the Building Stones of the Cathedral’, in Kelly, F. (ed.) Medieval Art and Architecture at Exeter Cathedral. London: British Archaeological Association, pp. 10-18.

- Salzman, L. (1952) Building in England down to 1540. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

4 Comments

[…] Find out more about stone and other materials used in medieval vaulting […]

[…] Find out more about stone and other materials used in medieval vaulting […]

[…] Find out more about masons’ tools Find out more about medieval building materials […]

[…] Find out more about cutting voussoirs, tas-de-charges and bosses Find out more about the materials used in medieval vaulting […]