Wells is a small city located in the northwest of Somerset. In 909 it became the seat for the new bishopric of Wells, though it was moved to Bath in 1090 and Glastonbury between 1197 and 1219 before finally returning to Wells in 1245. Wells was a local market town with some access to international trade, though it was not a port town like many of our other sites. The town is particularly famous for its surviving medieval fabric, including the extensive collection of buildings within the cathedral close.

Wells Cathedral

The cathedral church at Wells was first rebuilt under Bishop Robert (1136-66), but soon after 1174 a new architectural project was begun which resulted in the entire structure being replaced on a far grander scale. Work proceeded from east to west, funded by a series of grants and bequests as well as the income from a local market. The church was consecrated in 1239, indicating that a large proportion of the fabric had been completed, and the lower levels of the west end were certainly in place by 1243. Works proceeded rapidly, with the only break in construction being visible in the nave, probably the result of the interdict of 1209-13. The western parts of Wells were probably largely constructed during the 1220s and are widely attributed to Master Adam Lock, who died in 1229.

The chronology of the chapter house, Lady Chapel and central crossing tower of the church is contested, with two different chronologies being proposed. John Harvey and Linzee Colchester dated the plan and undercroft of the chapter house to the early 1250s, with the staircase and vestibule being dated c. 1264-80 and the chapter house itself c. 1295-1307. Whilst the Lady Chapel was described as ‘newly built’ in a document of 1326, they argued that it was instead completed c. 1319, whilst the central crossing tower was completed 1315-22. By contrast, Peter Draper proposed that the style of the staircase and chapter house vestibule was consistent with a date of the 1280s, whereas the rest of the chapter house being built during the 1290s and finished by 1307. The crossing tower was dated 1315-22, but the date of the Lady Chapel was adjusted to 1323-26 and was probably designed by Master Thomas Witney, who is known to have worked at other sites including Exeter.

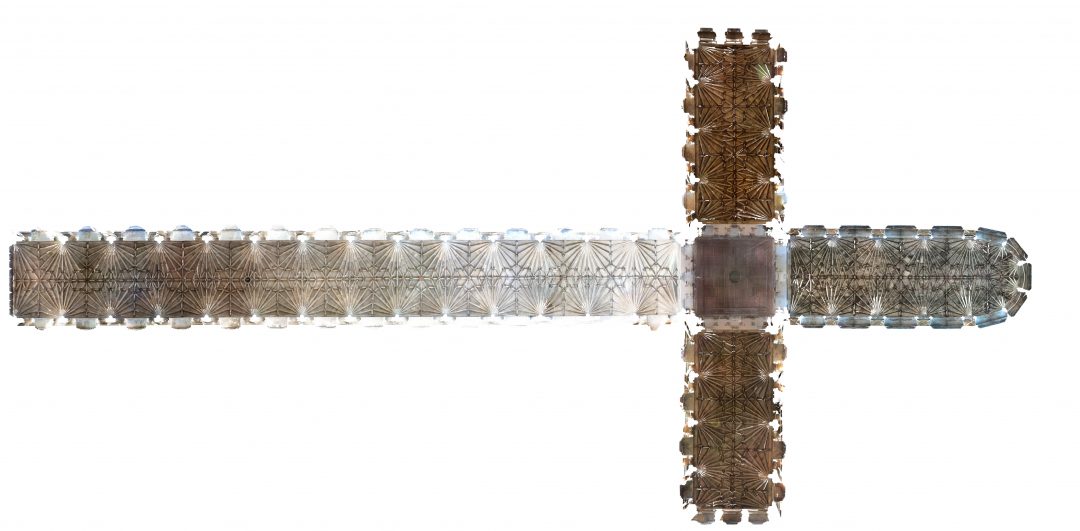

The construction of the Lady Chapel was the beginning of a more extensive reconstruction of the east end. The retrochoir and flanking chapels were likely in place by c.1329-31 and the choir with its elaborate lierne vaulting was probably in placed by the 1340s. The latter has been attributed to Master William Joy, who may also have been responsible for the scissor arches inserted into the crossing after 1338. Detailed study of the vaulting in the choir aisles reveals several different designs, suggesting that it was completed in a series of distinct phases, potentially by different designers. The three western bays have been attributed to Master William Wynford from c. 1365 onwards and further research may be able to test this proposition in greater detail.

Master Wynford also may have been responsible for the south tower of the west front, which was probably built c. 1385-95. The northwest tower was built during the 1430s, using funds left by Bishop Nicholas Bubwith in 1424. The burning of the spire in 1439 disrupted many ongoing works in the cathedral, necessitating the building of a new spire and tower which was finished by c. 1450.

Wells Cathedral Cloister

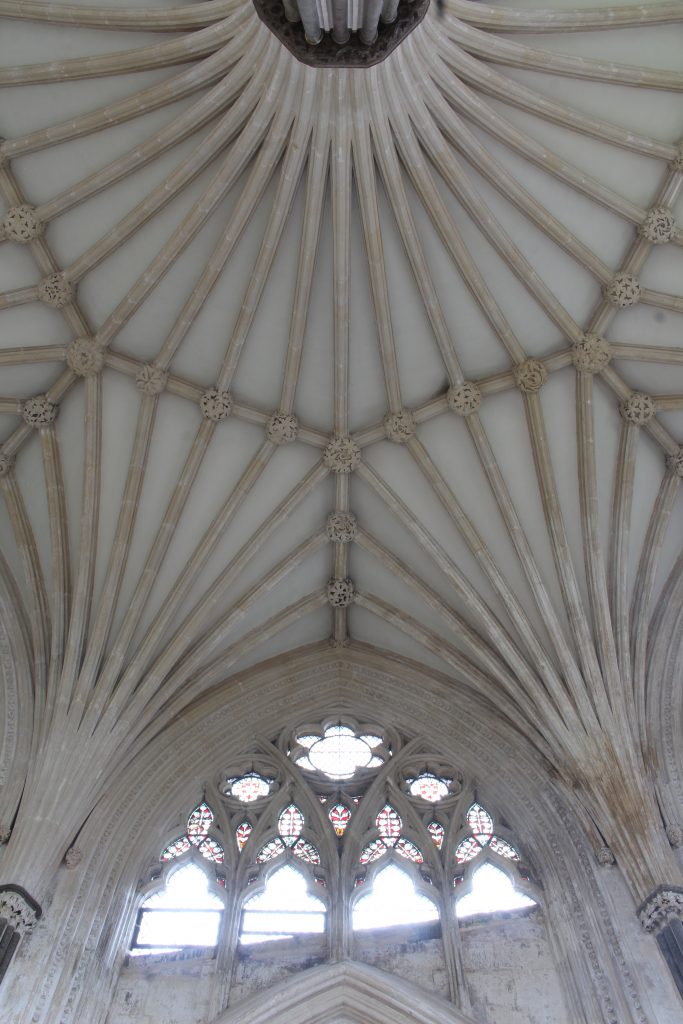

Work on the cathedral cloister was probably begun during the 1420s, starting with the east walk, which was almost certainly nearing completion in 1433. Construction may have been disrupted by the destruction of the old spire in 1439, but was resumed under the patronage Bishop Thomas Bekynton (1443-65), who may have been responsible for the west walk (though the heraldry of the bosses suggests that it may have been finished after his death). In 1457-58 the east walk and a single bay of the south walk were paved, suggesting that they were already vaulted at this point. Between 1477 and 1488 a large cruciform Lady Chapel was added to the cloister under the direction of Bishop Robert Stillington, designed by Master William Smyth. Finally, the remainder of the south walk was probably built c. 1490-1508 under the direction of Master William Atwood.

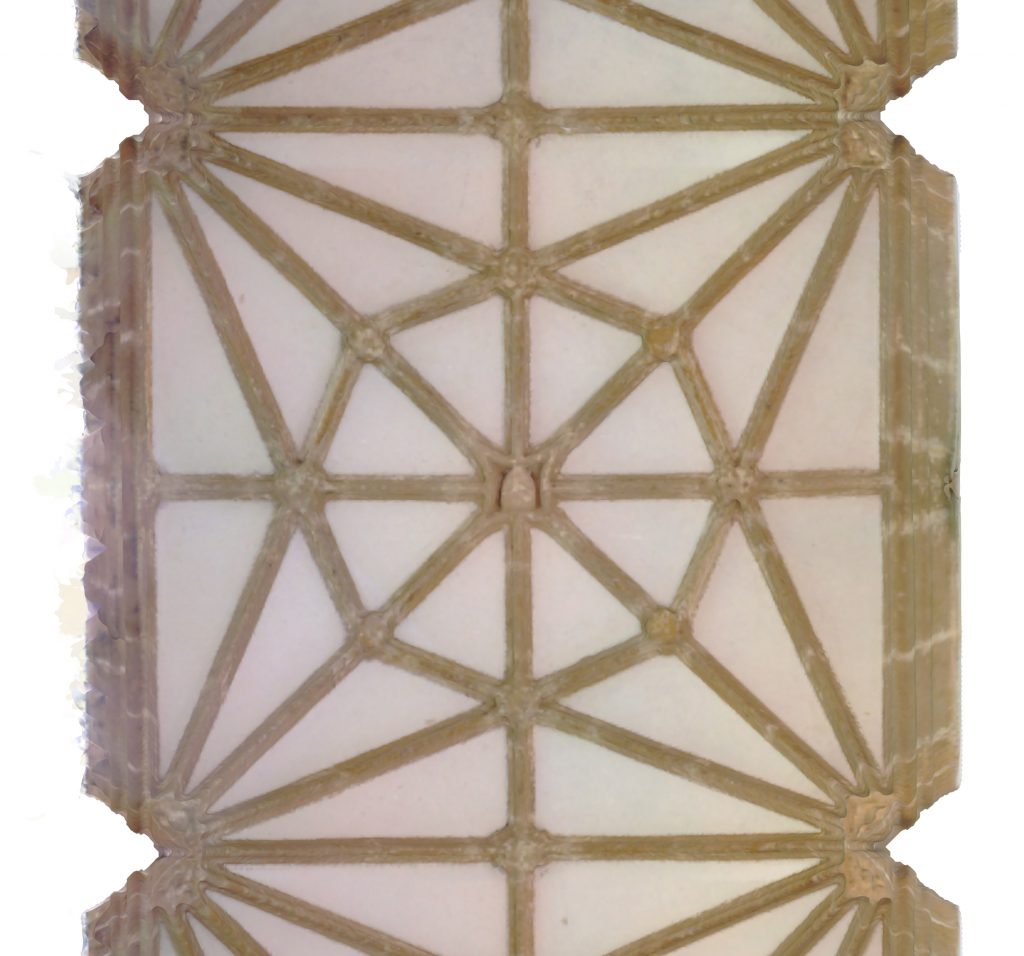

A design for the vault in the east walk can be found on a tracing floor located above the porch on the north side of the nave, accessible from the gallery on the internal elevation. It was drawn on a 1:1 scale, showing a quarter plan of the vault, the curvature of the ribs and the form of the tracery and window arch. This allows at least some of the lines on the tracing floor to be dated to the 1420s or so.

Further Reading

- Ayers, T. (2004). The Medieval Stained Glass of Wells Cathedral. Oxford: British Academy.

- Bilson, J. (1928). Notes on the History of Wells Cathedral. Archaeological Journal, 85, pp. 23-68.

- Buchanan, A. and Webb, N (2017) ‘Creativity in three dimensions: an investigation of the presbytery aisles of Wells cathedral’, British Art Studies, (6). [Online] [Accessed 7 October 2020]. Available from https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/index/article-index/wells-cathedral/year/2017.

- Colchester, L. and Harvey, J. (1974) ‘Wells Cathedral’, Archaeological Journal, 131, pp. 200-14.

- Colchester, L. (ed.) (1982) Wells Cathedral: A History. Shepton Mallet, Open Books.

- Coldstream, N. and Draper, P. (ed.) (1981) Medieval Art and Architecture at Wells and Glastonbury. London: British Archaeological Association.

- Crossley, P. (1981) ‘Wells, the West Country and Central European Late Gothic’, in Coldstream, N. and Draper, P. (ed.) Medieval Art and Architecture at Wells and Glastonbury. London: British Archaeological Association, pp. 81-109.

- Crossley, P. (2003) ‘Peter Parler and England: a problem revisited’, Wall-Richartz-Jahrbuch, 64, pp. 53-82

- Draper, P. (1981) ‘The Sequence and Dating of the Decorated work at Wells’, in Coldstream, N. and Draper, P. (ed.) Medieval Art and Architecture at Wells and Glastonbury. London: British Archaeological Association, pp. 18-29.

- Draper, P. (1995) ‘Interpreting the Architecture of Wells Cathedral’, in Raguin, V., Brush, K. and Draper, P. (ed.) Artistic Integration in Gothic Buildings, Toronto, Buffalo, and London: University of Toronto Press, pp. 114-30.

- Harvey, J. (1982a) ‘The Building of Wells Cathedral, I: 1175-1307’, in Colchester, L. (ed.) Wells Cathedral: A History. Shepton Mallet, Open Books, pp. 52-75

- Harvey, J. (1982b) ‘The Building of Wells Cathedral, II: 1307-1508’, in Colchester, L. (ed.) Wells Cathedral: A History. Shepton Mallet, Open Books, pp. 76-101.

- Morris, R. (1991) ‘Thomas of Witney at Exeter, Winchester and Wells’, in Coldstream, N. and Draper, P. (ed.) Medieval Art and Architecture at Wells and Glastonbury. London: British Archaeological Association, pp. 57-84.

- Robinson, D. (1928) ‘Documentary Evidence Relating to the Building of the Cathedral Church of Wells’, Archaeological Journal, 85, pp. 1-22.

- Rodwell, W. (1979) Wells Cathedral: excavations and discoveries. Wells: Friends of Wells Cathedral.

- Sampson, J. (2010) ‘Bishop Jocelin and his buildings in Wells’, in Dunning, R. (ed.) Jocelin of Wells: Bishop, Builder, Courtier. Woodbridge, Boydell, pp. 110-22.

- Webb, N. and Buchanan, A. (2017) ‘Tracing the past: A digital analysis of Wells cathedral choir aisle vaults’, Digital Applications in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage, 4, pp. 19-27.

- Wilson, C. (2011b) ‘Why did Peter Parler Come to England?’, in Opačić. Z. and Timmerman, A., (ed.) Architecture, Liturgy and Identity. Liber Amicorum Paul Crossley. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 89-109.

- Zee, E. van der (2012). Wells Cathedral. An Architectural & Historical Guide, Wells: Close Publications.

1 Comment

[…] Find out more about the history of Wells Cathedral Find out more about our digital surveying methods […]